Categories

One of the conclusions of the BEST-CLI trial (ref 1) was that of equivalency between alternate bypass conduits and interventions when a single saphenous vein is not available. I recently contacted Dr. Matt Menard to see if there had been subgroup analysis of these bypasses which represents a heterogeneous group of conduits including PTFE, PTFE with vein patch, spliced vein, composite vein, and even possibly allograft. The results from the abstract were intriguing -“83 of 194 patients (42.8%) in the surgical group and in 95 of 199 patients (47.7%) in the endovascular group (hazard ratio, 0.79; 95% CI, 0.58 to 1.06; P = 0.12) after a median follow-up of 1.6 years” with the primary MALE endpoint. If this was a football game, there would be a video review of the call. And they are looking at this, I was assured by Matt, but we would all have to wait for this year’s SVS VAM. Dr. Matt Menard is coming to speak at our 12th Annual Vascular Disease Update (link) which I highly encourage you to register and attend (addendum).

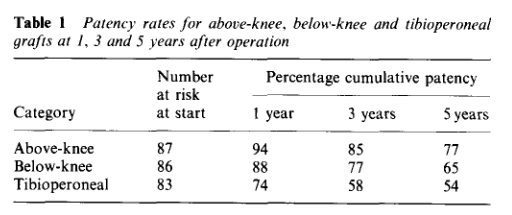

The Cohort 1 from BEST-CLI is an illustration of the vascular surgeons’ LIMA to LAD. It’s something we already knew from years of experience, but laid out in level 1 data (below).

The BEST-CLI paper is short on detail about cohort 2. This is where a lot of clinical decisions get made, and I suspect the vast majority of patients are getting interventions because fewer surgeons are facile with leg bypasses and vein patches.

Why the vein patch? While not a panacea for the lack of vein, from its inception, it has proved a worthy adjunct in limb salvage. Decades before endovascular therapies showed good limb salvage with modest to poor patency rates, Dr. Frank Veith showed that infrageniculate PTFE bypasses showed good limb salvage with poor patency (reference 2). Vein patches, such as the Taylor patch illustrated at the top, showed good patencies (reference 3) in an era where DOACS, DAPT, and statins were not available.

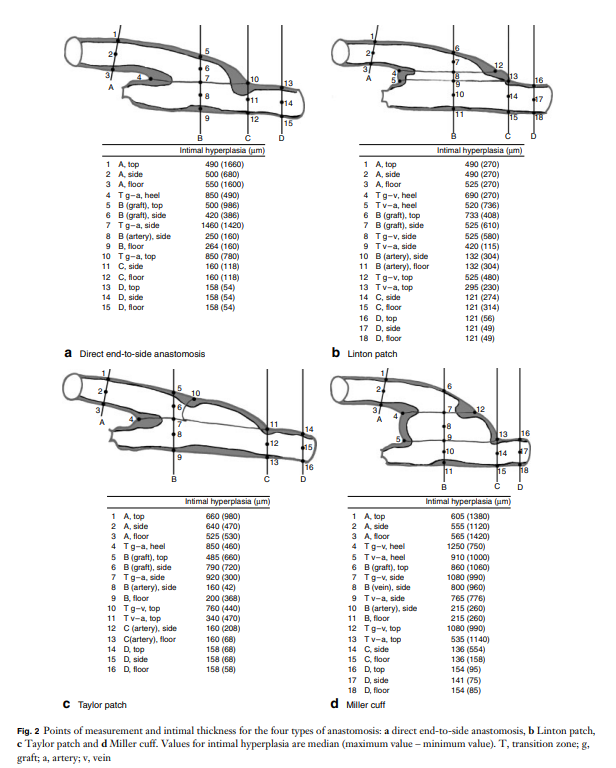

Why a patch works is debated. Some feel it is the modification of the end to side anastomosis that creates an optimal shape for containing turbulence which leads to intimal hyperplasia. This was the concept behind the Distaflo graft which I tried but have abandoned for not improving patency in my personal experience.

The best explanation of why vein cuffs work is from an animal study from Vienna. Intimal hyperplasia is best explained as a foreign body reaction and the reaction is worse with a true foreign body than with autologous materials. A simple anastomosis with PTFE to tibial artery creates a ring of hyperplasia. Vein patching moves this severe foreign body reaction off of the artery, leaving a gentler vein to artery reaction to occur on the outflow (reference 4).

My final point is that these surgical papers used to be the mainstay of podium presentation in the 90’s and ’00’s, but are now infrequent as the bulk of the time at these meetings is devoted to gadgets which almost always involves purchasing a box and contracting for disposables (the printer and ink business model). I am going to review our institutional results of these PTFE bypasses, and hope to see more from other groups. I look forward to the BEST-CLI papers to come, and other trials.

References

Addendum

The Annual Vascular Update at University Hospital has something for everyone, including a presentation on IRAD by Dr. Santi Trimarchi, and BEST-CLI by Dr. Matthew Menard. Local faculty from Cleveland are also featured in a broad review of vascular medicine and surgery chaired by Drs. Mehdi Shishehbor, Heather Gornik, and our chair in vascular surgery, Dr. Jae Sung Cho. Link. I will be presenting on neurovascular compression syndromes and renal failure/heart failure.

Reading this article on Vascular Specialist, the vascular surgeons’s Daily Prophet, “Likes, dislikes and reposts: The new age of the vascular surgery influencer” by Drs. Jean Bismuth (@jeanbismuth) and Jonathan Cardella (@yalevascular), they rightly point the spotlight on the trend of some vascular surgeons posting cases on social media for the purposes of self-promotion, virtue signaling, and influencing.

I can agree with their point that many of these posts are made by mediocre practitioners who display only the best and curated images, but I felt uncomfortable with the feeling that I may be one of those people being castigated for over-exposure on social media. They warn the readers of the dangers of misinformation fed to an uninformed public, but overlook the potential of social media for education and community. Being a vascular surgeon who has been on social media for over a 15 years, there are reasons why I am here which are not explained by this article, and I am compelled to elaborate on them.

Be the Lede

My journey started with hacking Google searches. My first job out of fellowship was a faculty position at my medical alma mater, Columbia P&S. The PR department asked everyone to compose a blurb for a web page and after searching on Google on how to rise in a Google search, I wrote out a paragraph full of the right verbiage to maximize my relevance on search. It wasn’t very difficult in 2002 to do this. Searching “vascular surgeon in New York” on Google after posting that info page consistently brought me up to the top five links, ahead of whole departments and many big names. I did over 400 cases my first year out, and I really felt if I could make it there, I could make it anywhere.

Bury the Lede

Unfortunately, like many vascular surgeons in New York, I got named in a lawsuit, and like many young surgeons with limited means and large loans to pay off, I couldn’t fight it and took the advice of hospital lawyers and settled. After that lawsuit, a Google search would return an article by the law industry PR around 2007, and I was at that point very busy in private practice in Iowa. It was so discouraging seeing that as the only thing speaking for me. I decided that I had to take an active part in shaping the message around me, to not let my Google search profile be defined by that article.

I decided to write and figured a few articles every week over a year would bury that article behind many better articles. I began to blog about something I am both horrible at but aspire to greatness in –golf (www.golfism.org). Writing about myself and my struggles in golf and being a young father and husband was how I found my voice. It was during this period that I found my best pieces were when I gave something of myself.

After finding my author legs, I began writing about vascular surgery, something I’m pretty good at but aspire to greatness in, on a personal blog (docparkblog, on Apple’s defunct cloud service). After a year, the blog got only 30-50 hits a day, at most 100. By internet standards, that’s low, and I kept my day job. After giving a talk at Midwest Vascular to an audience of about 50 mildly interested surgeons, that 30-50 engaged readers on my blog a day felt pretty good. A hundred was amazing. Medscape eventually tapped me for blogging on their site. My blog there, “The Pipes Are Calling,” was rated among the top 5 most read medical blogs in the world when I shut it down in 2011.

The Influencer

This social media presence generated influence -I was asked to participate in prominent research trials like PIVOTAL, CVRx, and CREST and others despite being in private practice. This is common now, but rare 15 years ago. The blogging did bury the lede. It eventually generated misunderstanding in the hospital administration at that time in 2011 and I was asked to stop blogging, at least until they could figure out what this internet thing was about. In 2012, I joined the Cleveland Clinic, I huddled with their social media department and came up with ironclad rules:

After launching www.vascsurg.me in 2013, I chose to focus on technique and opinion. I used my Linked-In and Twitter accounts to promote my articles. I always communicate in my authentic voice, although over the years, I’ve toned down the irony which is frequently misunderstood. In moving to my current hospital, University Hospitals, the first thing I did was arrange for a social media release and confirm what I was doing was okay. In reading the article by Drs. Bismuth and Cardella, in 2023, misunderstanding is still at the core of arguments against the use of social media.

The Worst

I have seen egregious examples of bad behavior on social media by physicians, as mentioned in the article. On my Twitter stream, I’ve seen people put stents in subclavian veins for thoracic outlet compression and wait for praise, which they get from similarly ill informed people who don’t realize I see patients like this several times a year with swollen arms and faces. While I was in Abu Dhabi, someone put stents in a patient from the common femoral to popliteal artery, and receive accolades for “minimally invasive skills” from all corners of the globe, only for me to remove the stents a month later and perform fasciotomies on the same patient -a middle-aged claudicator! There, I couldn’t post a rebuttal to the original case presentation because of local social media laws. Despite the word getting out, the surgeon only doubled down on his minimally-invasive fantasies. About the same time, I witnessed a relatively famous person self-implode on Twitter while accusing vascular surgeons of butchery (his words) by supporting open surgery over head to toe interventions. He got crushed by the general disapproval of his misrepresentation and personal bullying of a vascular surgeon, and then disappeared from social media. Evaporated. Good. We all have to do better.

The Best

I have also seen patients with rare diseases such as median arcuate ligament syndrome reach out and connect with each other and with physicians about diseases that aren’t taught in medical school or residency training on social media. There are Facebook groups, Twitter hashtags, and sub-Reddits, a rich communities of people who have to make serious decisions about their lives, many with limited access to specialists in their far-flung burgs and precincts. I think the fear is that bad decisions will be made based on bad information, but even in the highest, most rarified medical institutions, patients may get misguidance, have a complication, a poor outcome, in-person which can be worse than a social media interaction. If we value patient autonomy, access to the best information needs to be available. Social media lowers the barriers to access, for bad or good. Yes, it can do a whole lot of bad, but also an immense amount of good.

Keeping it Real

The authors are correct in that people will prefer to promote themselves rather than air complications and bad outcomes. The American surgical M&M process is an amazing and cherished tradition and protected process. It has no place in social media. Most surgeons also take the view that social media presence doesn’t lengthen your CV, it doesn’t bill. The many cheap suits of medical social media, the hawkers, the hucksters, the fragile egos will always be there on Twitter and Linked-In.

But other functions such as access and broad dissemination of information, experience, and opinion, are legitimate and critical. Comparatively few people get the message from a closed academic conferences and traditional modes of dissemination are slow. Most of the best social media posts are, as the authors mention, case reports. They fail to mention case reports under “open access” cost about 500USD to publish.

The peer review process, which I participate in, results in sometimes glacial turnaround times with papers landing often a year or more after presentation at a conference. I also learned from my time in private practice that these barriers block the voices of many legitimately great surgeons whose remarkable talents are only shared locally. I also learn from my time in academic practice that too many departments are not multiplicities of talents (Avengers Assemble!), but shops built around single personalities, who may declare that having never seen something, it cannot exist -to the detriment of those with unseen problems. Social media is the great leveler. Young surgeons can raise their profile, and non-academic surgeons can have a broader platform to share their expertise. If legitimately good people are dissuaded from participating, only the cheap suits will remain. As always, caveat emptor, et primum non nocere.

https://www.jvscit.org/article/S2468-4287(23)00014-X/fulltext

Innovation was a needed to avoid the coagulopathy that comes so frequently at the end of thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm repair in a low volume but fully resourced environment such as we had in Abu Dhabi. In this demanding disease, there are no shortcuts to success but every little bit of advantage helps.

There was an OpMed article on Doximity (https://www.doximity.com/newsfeed/1946e8dd-eddc-4eb4-aad6-46fe59c86da5/public) which reports that 69% of 58,000 physicians surveyed said they would provide emergency care. That number is depressingly low at first view but can be answered by asking how many of us are ATLS, ACLS, or BLS certified? A quick search fails to give a result, although various pro CPR groups have on their websites that all caregivers should be trained in BLS. The darker question is how often do fully trained and certified physicians choose to withhold care and hide their identities?

I can give you a quick answer. Most doctors will sit on their hands when the PA announces “is there a doctor on the plane?” hoping that someone else will raise their hand. Back when I was a second year surgical resident, I took a vacation with my wife to London and Paris. On the flight, over the Atlantic, the cabin crew asked for any medical assistance. Before I had a chance to contemplate the question my wife jumped up and pointed at me and shouted “He’s a Doctor!”

I was in shorts and hoodie, with a baseball cap. Back then in my late twenties, I looked about 15 years old. The British Airways stewardess looked at me dubiously, then looked around behind me to see if any other hands were raised. <sound of crickets>

She escorted me up the stairs to first class and in one of the giant chair-and-a-half recliners was a pale fellow in a nice suit, diaphoretic, dyspneic, and maybe a little drunk. He couldn’t speak well but was awake and maintaining his airway. His radial pulse was thready and weak. I pressed the button that fully reclined him into a bed, not a little jealous.

“Are you having chest pain?” <head shake>

“Do you have pain anywhere?” <head shake>

“Are you diabetic?” <¯\_(ツ)_/¯>

Cold, clammy, dehydrated, drunk -hypoglycemia was my diagnosis. I asked the stewardess if they had any tubing, a funnel, and orange juice -because that is how you deliver sugar to someone who can’t protect their airway. I was an enthusiastic PGY2 and the orange juice enema was one I was eager to roll out. She looked at me funny and handed me a large black leather suitcase -the kind you see sniper rifles disassembled and packed. In it was a pretty thorough crash cart with defibrillator, airways, Mac blades and handles, bag mask, IV’s, bags of saline, and boxed syringes of code meds including D50. Oxygen was available. It was British Airways first class after all.

I looked around and saw no great place to hang an IV, so I grabbed the D50, horse needle and all, and found his cephalic vein and injected the whole vial. The change was instantaneous -the eyes which were spinning beachballs, stopped wobbling and focused. All that was missing was that Apple Macintosh “bongggg” sound. I gave the fellow a gauze and instructed the stewardess to give him orange juice spiked with sugar.

“Shall we land?” asked the stewardess. The neighboring passengers, all dressed as if for a fancy cocktail party, looked at me with eyes that said, “We really need to get to London.”

“Where are we?” I asked.

“Over Reykjavik. The captain needs to know now.”

I look at my patient, and he had unreclined himself in his fancy leather loveseat, and shook his head. “Thanks. I’ve got to get to London for a meeting.” He was going to be fine. I recommended he see someone for his diabetes (which he confessed to neglecting), and I walked downstairs and back to my seat in steerage.

A older couple (I’m sure they were middle-aged like I am now) was next to us and the lady smiled, and the man leaned over and asked, “how did it go?”

“Hypoglycemia. Are you a doctor?” I says.

“Why yes, a cardiologist. We’re going to London for a conference!” he chirped. I think he caught that I was giving him an accusing look, and added, “you’re wife volunteered you so well, so enthusiastically, I figured you had it well in hand. Good job.”

I sat down and my wife immediately asked, “did you ask them to upgrade us?”

“No.” That is the advantage of a wife when she isn’t volunteering you for missions, she’s looking out for your interests. I was going to make some grand statement of my purpose in life, but was interrupted. The stewardess came up with a brown bag full of tiny bottles of liquors, spirits, and whiskeys, which made me very happy, but my wife just rolled her eyes.

“You would have been happy with a cookie,” she hissed. “Why didn’t you ask for an upgrade? What’s wrong with these people?” And I thought the same, for a different reason. Seated all around me were likely cardiologists headed to London for that conference. Just counting bald heads, there were at least twenty.

Now, nearly thirty years on, I don’t blame those fine folk for not being quick on the draw. I am sure one of them would have stood up eventually, but the last thing you want to do on vacation is work, and what I did upstairs in first class was not much different from the work I was doing every other night on call (this was 1995).

Now, in the middle of my career, there isn’t much that gets my blood running, so I empathize with the festive, sanguine attitudes of the many physicians probably on the plane with me, headed for a nice holiday and conference in London. Some happy fellow jumps up and takes care of the problem, so no need.

Also, I’m not shy in crowds or stressful situations. Everyone in first class was watching me get venipuncture with the D50 syringe and the horse needle which was easy because the fellow was so thin. At that point in my life, screaming HIV positive crack addicts fighting you while getting central lines and spinal taps were the norm. I suppose I couldn’t fault someone more bookish and scholarly for not standing up right away. I assume 69% would have.

I’ve been called about a half dozen other times on planes. It used to be my wife volunteering me, but over the years, even she has taken on a bit of a glazed attitude. The last one a few years ago was a poor fellow whose wedding ring was causing an ischemic finger, made worse by traumatic attempts at removing the ring. Soap and rubber bands fixed him. It barely elicited an eye roll from the spouse who did not volunteer me that time. It was one of those cheap airlines in the American Southwest and I got nary a thanks.

I have never contemplated the medical malpractice ramifications of rescuing someone, saving a life. I assume something like sea-law prevails up in the air, where the captain can marry folks and push them off gang planks, where decency, need, and common sense prevails over tort law. Unfortunately, I have never seen another black suitcase since that first time on British Airways, and the pre-9/11 days of carrying a pocket knife are long gone, making emergency surgeries and fashioning of MacGyvered medical devices impossible. The idea of embarking on supporting the life of someone when the last time you ran a code was in medical school may be too much to ask someone, and doing the wrong thing may be worse than doing the right thing badly.

Did you know you can fix a tension pneumothorax with a pen, a rubber band, and a condom, with the appropriate knife and fortitude, and maybe a tiny bottle of vodka.

But isn’t that why we went into medicine? To save a life is to save the world, the Talmud tells us, and we can be heroes, if just for one day.

The patient is a woman in her forties who works hard and smokes cigarettes to find stress relief. The year prior to presentation, she began to get cramps in her calves while she walked the halls of the building she cleaned, and this became unbearable. A consultation at our hospital revealed moderate to severe diffuse atherosclerosis without a dominant lesion but notable small distal aorta and iliac arteries with a 50% stenosis of the left iliac origin. Recommendations were to quit smoking and exercise. She found this difficult to achieve and went to another hospital nearby.

There, 6 months prior to presentation, she began complaining of painful cyanosis of her toes which was described as blue toe syndrome. These outside studies were not available. She was taken to the OR and her common iliac arteries were stented. This gave her relief, but the soon pain returned three months later -her stents had occluded. This was treated with more stents, extending them proximally into the aorta and distally in the case of the right across the iliac bifurcation. This afforded her relief for three more months until one weekend she found herself unable to walk again for more than minimal distances, and she took herself to my hospital, University Hospital, Cleveland Medical Center.

On examination, she was a large woman with no femoral pulses, but signals could be obtained in her popliteal and tibial arteries. Her PVR’s showed inflow disease and poor flow at the feet.

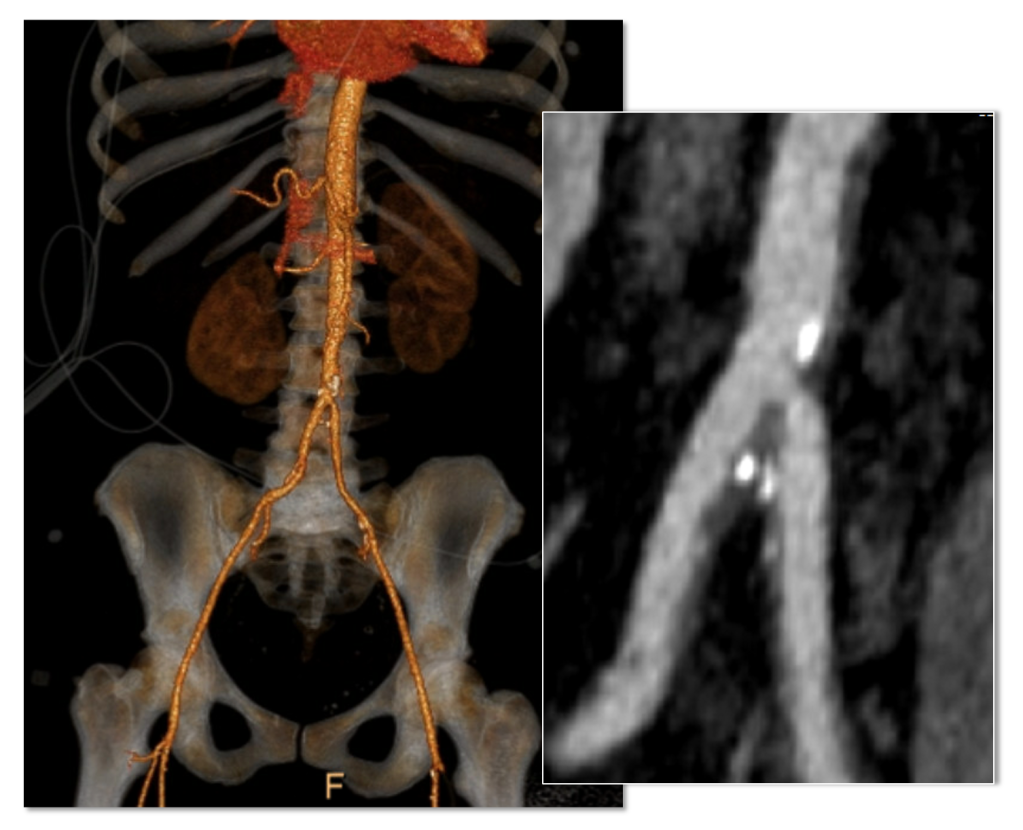

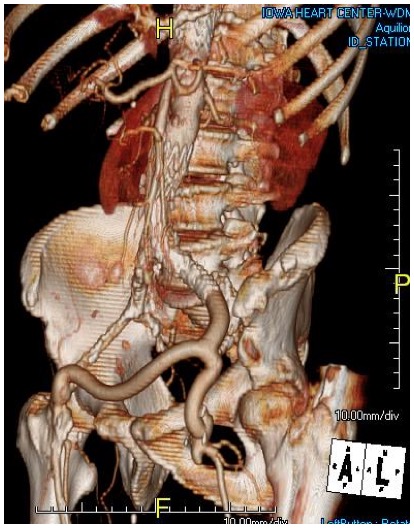

Her baseline CTA in workup of her claudication the year prior to getting stented shows the aorta and iliacs, while open, are small, with aortic lumen diameter reaching 10mm and common iliac lumen diameter at 6mm with diffuse atherosclerosis (below).

The CTA on presentation shows bilateral stent occlusion. A closer look shows the second set of stents extending the original stents both proximally into the aorta (raising the bifurcation) and distally into the external iliac and across the internal iliac origins (white arrows). The internal iliac arteries, despite the stents and on the right thrombus in the stent, supply flow to the external iliac arteries which have not thrombosed.

The treatment options were

Although exercise and risk factor modification should be part of the treatment regimen, the best time to institute this was before her first intervention. With the long segment occlusion of her stents, coverage of the right internal iliac artery and occlusion, and acuity of her symptoms, this is no longer feasible.

It reveals a certain kind of bias when we prescribe walking exercise to those who can’t afford gyms or equipment, and whose neighborhoods are unwalkable.

Reintervention, having failed once, will not be durable. Even with anticoagulation, any recanalization -thrombolysis, thrombectomy, balloon angioplasty, atherectomy, lasering, and restenting, would not be durable.

It is likely the patient is frequently vasoconstricted and this is exacerbated by smoking. While never diagnosed with Raynaud’s, she did give a history of easily have numb, cold fingers and toes in the chilly winters in Cleveland. Even normal spectral Doppler signals will show pauses in flow in the peripheral arteries. Combined with any hypercoagulability and injured lumenal surfaces from interventions, and stents will go down.

An Aside on Small Aorta Syndrome in Women

One of the advantages of being a village elder is you remember forgotten concepts that guided treatment “back in the day.” The small aorta syndrome defined as having an aorta smaller than 12mm in diameter is one of those. Best described as not having enough pipe -imagine a small caliber fuel line throttling an engine. For all the muscles involved in standing and walking, there is a minimal diameter necessary for function.

Small aorta syndrome stands up to objective testing. A patient with a small aorta but otherwise patent lower extremity arteries, can present with claudication and demonstrate drops in ABI with exercise. These are typically female smokers with elevated BMI. Along with their small aortas, their external iliac arteries will be small, and I used to wonder if some critical period of inactivity in their early years failed to grow these arteries, or if this process of normal growth and remodeling is retarded by smoking.

Small aorta was a common indication for aortobifemoral bypass (ref). Unlike some abandoned indications for operation like “4.5cm AAA” and “asymptomatic 60% internal carotid artery stenois,” it had a testable finding of drop in ABI with exercise, but its acceptance has waned in the advent of the endovascular era. In a purely open era, I think there was greater emphasis and awareness on engineering the hemodynamics. While endovascular interventions simplify treatment, just stenting a small arteries usually doesn’t fix the problem as illustrated in this case. That is because there is a maximum size that the arteries receiving the stents will allow.

The iliac artery and aortic bifurcation will only tolerate so much upsizing with stents before rupturing. The interventions are constrained by the size of the adventitia. What is also ignored is the concept of elasticity -the 7mm lumen through a reopened and restented artery provides more resistance to flow than a 7mm artery restored via endarterectomy. All stents decrease elasticity of the circuit and decreases flow in a pulsatile circuit because of the increased impedance. Bovine pericardial patches on the other hand add elasticity. Endarterectomy restores elasticity. .

Enough Pipe

In the early 2000’s, I used to live in an pre-war apartment in Riverdale down the hill from Drs. Takao Ohki and Frank Veith. The apartments above and below me all shared this same feature -poor water pressure, because during a restoration twenty years before, the owner used the wrong, smaller size of pipe for this line of apartments. The taps would run, but if more than one apartment ran the shower or dishwasher, the taps would drip. The apartments would claudicate. The pipes were all patent, but inadequate. Not enough pipe. This patient endowed with small vessels, grew a large body, and smoked, and her muscles needed more pipe to support the added load. Not enough pipe.

So is the solution an aortobifemoral bypass? It is the board answer and a durable one, but it shares with axillobifemoral bypasses the risk of groin infections, particularly with a large body habits (below). The outflow arteries, all patent, are small and likely subject to vasoconstriction. My choice of ABF graft in this patient is a 14x7mm bifurcate which is on the small side, but I would be afraid that a 16x8mm graft would be too large on both the aortic and iliac side, resulting in mural thrombus formation.

Axillo femoral bypasses, aside from the groin issues, suffer from poor long term durability and is not a great choice for a 40 year old. Her axillary artery was 6mm and sourcing flow to the lower torso from that is never great. Also, supplying a long 8 or 10mm graft would recapitulate the original problem of a small aorta. Not enough pipe.

For me, the best option would be to remove the stents and restore the distal aorta and iliac arteries to their original elasticity and slightly larger than original diameter. I would then be able to reopen flow to the occluded right internal iliac artery. Not just enough lumen, but enough and correct pipe.

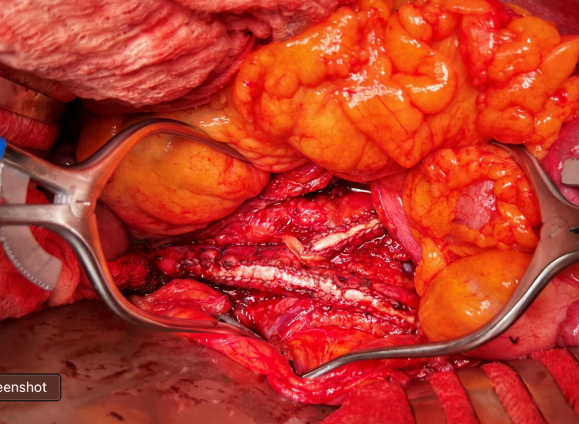

Technique: Exposure

Exposure is predicated on the planned extent of the endarterectomy, place for clamping, and plans for aortobifemoral bypass if the endarterectomy results in poor adventitia. In a woman, the iliac bifurcations are easier to reach. A midline laparotomy is the incision of choice here. Let me digress here about the laparotomy. Over the three decades since the launch of laparoscopic surgery and subsequently endovascular surgery, the midline laparotomy has gotten an undeserved bad rap. Laparotomies are well tolerated and should not be viewed as a rare bailout or outright failure of laparoscopic therapy. Rather, it is still the gold standard exposure.

The infrarenal aorta to the right external iliac artery is exposed as well as the common iliac. In this patient the sigmoid mesentery was fatty and did not readily expose the iliac bifurcation so a separate exposure of the distal left common iliac artery was performed by mobilizing the left colon.

The aorta above the bifurcation was prepared for clamping. This involves circumferential exposure as I prefer a transverse aortic cross clamp. The lumbar arteries are clamped with bulldogs or aneurysm clips. The right external iliac well beyond the stent is controlled and the internal iliac is exposed and controlled. On the left the internal and external iliac arteries are expose and controlled.

The patient is heparinized clamps applied, and I make the arteriotomy with a 15 blade cutting down to the stent. The aorta is cut to a point about a centimeter below the clamp. The external iliac is cut to where there is patency of the artery and the plaque is mild. The endarterectomy is performed in the same way one does a carotid or femoral, with care to find the correct endarterectomy plane outside the plaque and good end points where the plaque adheres well. The internal iliac plaque on the right was chronically occluded but was successfully removed via eversion resulting in back bleeding. I sound the artery with a dilator to make sure a dissected plaque isn’t occluding it then reclamp.

The left common iliac artery is opened via a separate arteriotomy as I find tailoring a Y-shaped patch laborious. The arteriotomy is extended under the sigmoid mesentery and then moving the left colon medially the arteriotomy is finished slightly beyond the external iliac origin. The endarterectomy is finished short of the iliac bifurcation and any narrowing at the bifurcation is treated with the patch.

The specimen shows that the adventitia remains separated from the stents by the plaque. I rarely use tacking sutures as I feel a properly performed endarterectomy results in no plaque or well adherent mild plaque.

The patch needs to be thoughtfully applied. An overly large one will billow, and at worse case, create an artificial aneurysm. For example, for a 7mm iliac artery, the circumference is 22mm. Adding an 8mm patch with 1mm suture bites results in a 26mm circumference and an 8.3mm end diameter. Narrower is okay, but much larger will result in size mismatch that the body compensates for by laying mural thrombus. A long 8mm wide patch can be cut from a large swatch of bovine pericardium, remembering to add a slight angulation onto the iliac artery.

This operation avoids the groins with exposure or access into a small artery with a large sheath. A 4mm artery with 12.6mm circumference receiving an 8F sheath receives a 2.6mm hole, a 40% defect across the anterior hemicircumference of 6.3mm. This is not trivial, particularly because the arteries are often atretic after prolonged occlusion, may tear with a closure device, most of which are off IFU for such a small vessel. Avoiding the groins altogether is a great benefit to this type of procedure.

A postoperative CTA showed wide patency of the restored aorta and iliac arteries.

At followup several months after the procedure, the patient was walking well without claudicating and was ready to return to work. PVRs showed excellent flows down to the toes.

Hemodynamic Engineering

A surgical trainee has to develop a sense for flow. Looking at a circuit, she has to ask “how does blood get from point A to point B?” Merely providing a pipe does not mean a cure. For example, replacing a blocked artery with a steel pipe would provide flow but it has a hemodynamic impact that is different from the native vessel. Flow stoppages during the cardiac cycle that is modulated in a normal artery by the elasticity of its wall. While we don’t deliver steel pipes, we do something similar in ballooning heavily calcified arteries, or stenting them. ABF with prosthetic bypass offers a safe, broadly available method of treating this, but is fraught with problems for patient who develop groin infections or occlude a bypass for the reasons previously mentioned. Endarterectomy and patching with bovine pericardium allows for more precise restoration which would be a laudable goal in a young patient.

And my final point is this. This patient can yet undergo aortobifemoral bypass. Ironically, even larger stents may be safely placed than was previously possible. One of the principles laid out by Dr. Jack Wylie in his peerless surgical atlases was of leaving a patient in a condition to allow for future necessary operations. For a forty year old patient with many decades left, this is a critical concept.

This case represents the second aortoiliac endarterectomy I performed to remove failed stents. The third just happened today with resection of failed CERAB stents which I did with my chair and fellow Mayo Alum, Dr. Jae Cho. I think that there is a room for this operation which should not remain in the history books.

For a video presentation from Dr. Pat O’Hara: https://vascsurg.me/2022/10/15/aortoiliac-endarterectomy-removing-occluded-stents-is-possible/

References

Cronenwett, JL, Davis JT, et al. Aortoiliac occlusive disease in women. Surgery 1980; 88:775-84.

At the VEITH Symposium, which I attended briefly last week, while I foraged for lunch and sought out friends, I wandered into a crab trap (diagram above). Or more specifically, the WL Gore exhibit hall (below).

The coffee and bevarages featured all day, and the steak buffet at lunch, draws people in, like the smell of chicken to a crab, and once you have a plate of food, you then are kind of committed to moving forward into the conference room where they have a video feed of aortic symposium and tables to gobble your lunch.

Like a hand reaching into a crab trap to retrieve the catch, the reps wander in and chat you up, but thankfully only if they know you, which is fine because any hard sales tactic would trigger a fight or flight reflex that would ruin the generally chill atmosphere. There are exits to the left because, you know, fire codes, but they are small, and going out the way you came in risked bumping people juggling plates of their lunch, cups of their coffee. So you go in, sit down, and nibble, watch someone you vaguely know up on the big screen who just decided to go full head shave bald (why is that a thing?), check your phone and find out your friends are in another trap on the other side of the center. And their doors are closed, invitation only. Silly crabs.

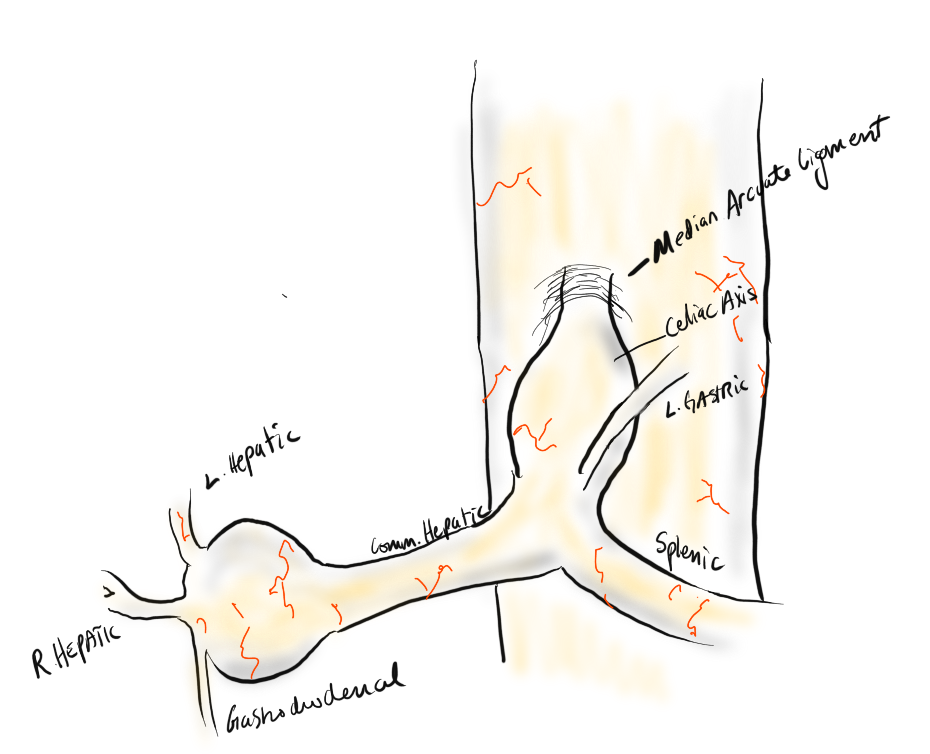

Median arcuate ligament syndrom (MALS), also known as celiac axis compression syndrome (CACS) and its eponym Dunbar Syndrome, is manifest as epigastric abdominal pain and a compendium of symptoms, arising from chronic compression and inflammation resulting from compression of the celiac plexus between the median arcuate ligament and the celiac axis.

The diaphragm muscle descends from the neck during development (the phrenic nerve originates from C3-C5 nerve roots), and in perhaps up to 25 percent of individuals, drapes across the origin of the celiac axis, and sometimes anchors further down impinging on the SMA or renal artery origins.

While a significant number of patients have this coverage of the celiac axis origin, not everyone has pain. Some whose celiac axis is compressed develop post-stenotic dilatation. For some of these, there is damage to the celiac axis resulting in intimal injury, dissections, thromboses, webs. Turbulent flow causing post-stenotic dilatation in the celiac axis can proceed to aneurysm formation. Downstream in the splenic and hepatic artery and its branches, turbulent flow can engender tortuosity (lengthening) and aneurysms (widening). This disease subset of celiac axis compression should be termed aMALS (arterial median arcuate ligament syndrome).

Both arterial and neurogenic manifestations of celiac axis compression are under the same ICD code of I77.4, referring to both celiac axis compression syndrome and median arcuate ligament syndrome. While I would never suggest more ICD codes, there should be a differentiation similar to the other compression syndrome, thoracic outlet syndrome (TOS). The pain-based syndrome, which is more common, should be termed neurogenic MALS, or nMALS, and the arterial disease secondary to celiac axis compression should be termed arterial MALS or aMALS. The treatment of nMALS is surgical ablation of the celiac plexus along with median arcuate ligament release, done via open, laparoscopic, and robotic techniques. The treatment of aMALS is the treatment of the arterial complications of celiac axis compression and should involve median arcuate release and treatment of the arterial pathology with either open or endovascular techniques.

Case Presentation

The patient is a middle-aged man with several months of right sided abdominal pain, mostly in the right midaxillary line at the costal margin, right upper quadrant abdominal pain, and right sub-scapular pain. He did not have gallstones, and had no gastrointestinal complaints. He is hypertensive and was on a single agent which he took in the mornings. His pain began during the day and crescendoed in the evening. His prior visits to the emergency room had revealed a hepatic artery aneurysm and celiac axis aneurysm. In the ED, his examination was significant for pain and mild tenderness in the right upper quadrant of his abdomen. He underwent a CT scan.

The CTA showed compression of the first centimeter of the celiac axis by the median arcuate ligament of the diaphragm and mild post-stenotic dilatation to 14mm. At the terminus of the common hepatic artery, where the hepatic bifurcated was a 2.4cm aneurysm with mural thrombus. With blood pressure control, his pain remitted.

The trainees and I had a lively discussion as to indications for repair and whether this constituted a symptomatic aneurysm. As I have stated in past posts, all pain has a nerve and a mechanism for pain. Abdominal pain and its points of referral are well known going back to the 19th century and encapsulated in Cope’s Early Diagnosis of the Acute Abdomen, whose most recent steward, Dr. William Silen just passed this September. Processes involving the gallbladder and nearby hepatic artery refer to the right upper quadrant abdomen, right chest, right shoulder and scapula which was where the patient’s pain was. And it improved with controlling his hypertension. There was no question to me the aneurysm was symptomatic, likely from strain on the aneurysm.

The question then devolves to whether this is to be done endovascularly or open. While it seems straightforward for me, I have realized at large meetings there will always be some endovascularist proposing something. For me, to exclude pressure from the aneurysm and avoid rupture, the aneurysm had to be isolated from the blood flow and pressure. Ideally, this would be done with tiny covered stents.

There are no 7mm x 4mm stents bifurcation stents.

Embolization of the hepatic aneurysm, which is done for the splenic, offers hazard of hepatic ischemia. Despite what is written in the textbooks about the portal venous system providing most of the perfusion of the liver, you have to remember there is only portal flow when there is food. Acutely losing one of the hepatics, even clamping it for a time, reverberates as a spike in the LFTs, along with attendant systemic inflammatory response. While the liver, like spleen, can recover and regrow, you mess with it at your great peril. Based on the CTA, closing the hepatic artery with coils and plugs will likely be tolerated as hepatic flow would continue via the gastroduodenal artery which is not small, but there is no guarantee that the aneurysm wouldn’t be pressurized yet by the prominent GDA (if you disagree please feel free to comment).

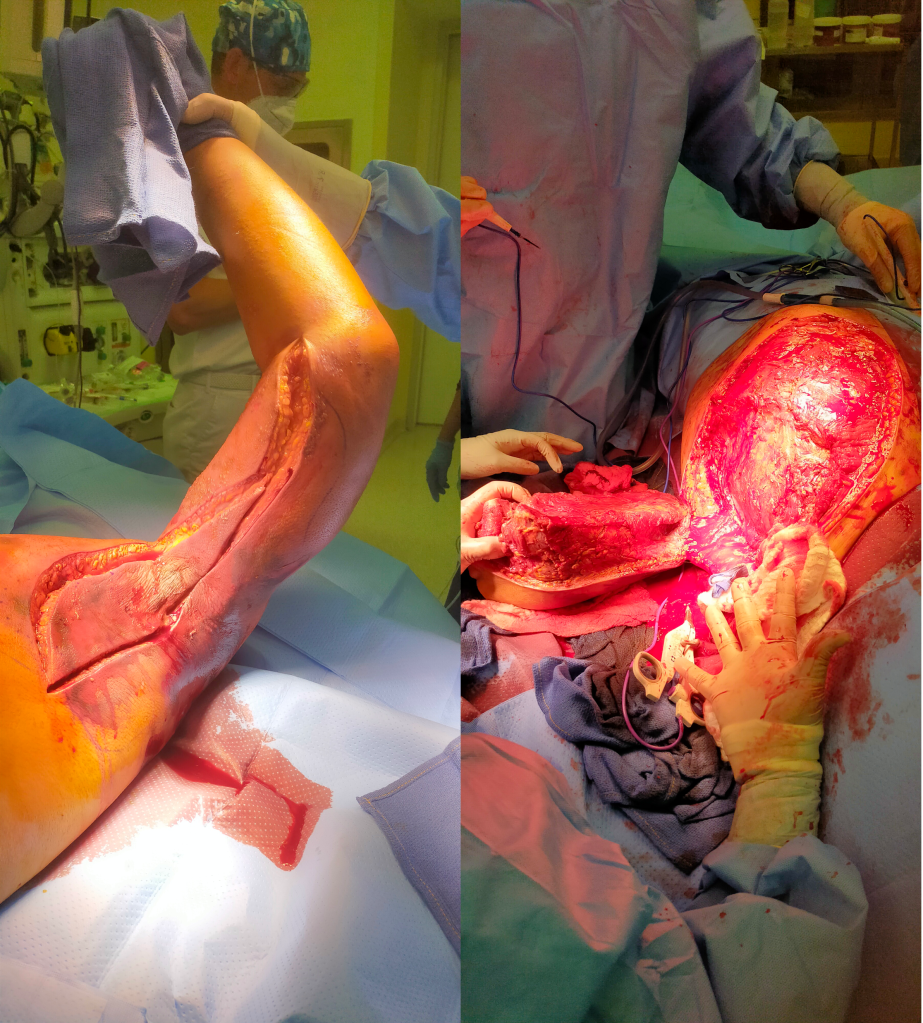

He was prepared for surgery with echocardiography (normal) and lab testing (normal LFT’s, CBC, BMP, INR), and taken to the OR. A chevron incision was made to broadly expose the area. The median arcuate ligament was exposed and released -there was dense tissues proximal to the dilated celiac axis. The aneurysm was dissected out and the small branches were carefully dissected out and controlled. It is easy to injure the branch hepatic arteries which can constrict on dissection.

A suitable length of saphenous vein was harvested and prepared. The three vessels diagrammed above did not present themselves suitable for a single Carrel patch so I sewed end to end to a patch incorporating the right hepatic and gastroduodenal arteries, and performed a sequential side to end anastomosis to the left gastric artery.

The patient recovered well and was discharged home on POD#5, and in followup had no further symptoms.

Discussion:

The differentiation of arterial and neurogenic manifestations of MALS is an important refinement of our understanding of this disease, which I believe to be a byproduct of our bipedal lifestyle. The lordotic curvature of the spine, necessary to balance our upper torso on a vertical spine, pushes the spine forward and applies tension to the median arcuate ligament, along with other structures such as the duodenum and left renal vein in superior mesenteric artery syndrome and nutcracker syndrome, and the left iliac vein in May-Thurner Syndrome.

This compression is not only enough to narrow the celiac, but injure the artery by crushing. Stenting here does not do well because of the external compression and even after release, the artery may be damaged and require repair.

The chevron exposure heals well and is well tolerated and offers perfect exposure. While I was doing it, it occurred to me that a laparoscopic bypass is technically possible, and may be preferred to the long incision. Recent multi-institution study of MALS treatment would suggest laparoscopic approach offers a lower complication rate compared to open surgery (ref 2.)

The critical thing is having more surgeons recognize the compression that occurs in the abdomen and manifests in disparate and unconventional ways. The key is tying pain to a lesion, a mechanism, a nerve, just the way Cope’s does.

References

5 Top FAFO’s In Vascular Surgery

In no particular order, I list these problematic situations that are outsized in their ability to take a case sideways.

5. Iliocaval venous injury, particularly small tributaries going under aorta or around its branches. While not pressurized, they have tremendous flow like a hole in a plastic bag holding a goldfish, and without precise control, you are as likely to widen the hole or make more holes as you try to suture the holes. I’ve had some success using the Park clamp (link). You can’t buy one but you are free to have one made by your local smith. Otherwise, you need to keep your finger on the hole while you call in help, usually in the form of more vascular surgeons to get exposure and the vein properly clamped for repair.

Add yours in the comments below.

I had posted the above picture from over 15 years ago during my time in Iowa of my hybrid AUI-Fem-Fem (under unclampable 2, link). This technique came back to me as I was strategizing the upcoming aortic revascularization of a patient with iliac occlusions with the added complexity of an ileal conduit in the right abdomen. He had multiple failed prior iliac stents and failed femorofemoral bypasses -his right CIA and EIA were occluded while the left EIA had become occluded resulting in ischemic rest pain. While the picture alone is sufficient for me, it was brought to my attention by Dr. Joedd Biggs, fellow alum of the Mayo Clinic, on faculty at University of Kansas Hospital, that more detail was needed. So while resting my tired dogs, I got on my tablet and drew it out. Joedd, I present you my technique for a hybrid AUI-Fem-Fem bypass of the aorta.

The image above shows the necessary incisions for the femorofemoral bypass and the retroperitoneal pelvic (transplant) exposure of the left iliac bifurcation. I nearly always make oblique rather than vertical skin incisions in the groin to avoid wound complications from incising the inguinal crease orthagonally.

A left lower quadrant retroperitoneal exposure of the pelvis is performed -this is a standard renal “transplant exposure.” The two groin incisions are made and the common femoral arteries are exposed. Endarterectomy may be performed, although if the orifices of the SFA and PFA are patent, I don’t. The bypass graft is tunneled retropublicly and this is facilitated by the transplant incision. I generally use a 7mm ringed PTFE graft. Once done, the common iliac artery is divided above its bifurcation and the bifurcation is oversewn or stapled. A 12mm bypass graft is then sewn end to end to the common iliac artery (below).

Through the conduit, a suitably chosen iliac limb of an EVAR system is brought through to the aorta and deployed with its end across the anastomosis into the conduit. A Gore Excluder 12mm ending iliac limb is ideal as its proximal end is appropriately sized for the diseased abdominal aorta. The limb is then aggressively ballooned to profile, particularly in the 12mm graft (below).

The 12mm conduit graft is then sewn end to side to the femorofemoral bypass (below), completing the AUI-Fem-Fem.

I believe there are hemodynamic advantages to this over reintervening on native aortoiliac segment. First, size does matter, and until a suitable aortoiliac occlusive disease stent graft system is engineered, this represents an optimum. The Gore excluder graft limb is 16mm proximally and this is usually more than enough to diameter for the diseased abdominal aorta. The end diameter of 12 or 14.5mm will seal nicely in a 12mm conduit. I have not used a 16mm conduit only because I prefer not rupturing the aortic bifurcation with the “aggressive ballooning” mentioned above. The 12mm diameter is the boundary above the “small aorta syndrome” diameter of 10mm.

If the iliac is occluded, a wire can be driven through it from above and the conduit sewn over it. The iliac limb can be delivered after some pre-dilatation then followed by the “aggressive ballooning” of the iliac limb. The deployment into the conduit creates a stable “endo-anastomosis.”

Patients like my upcoming patient usually fail intervention due to the lumen size issues. An 8mm fem-fem bypass fed by a diseased series of iliac stents with at most 7mm lumen diameter is a recipe for the development of mural thrombosis and occlusion. The lower half of the body are fed by the diseased conduit of the donor EIA. This way, true aortic inflow is created.